The only thing that scares me is that I will die tomorrow without having known myself.

— Blind Owl by Sadeq Hedayat

For a long time, I wondered which is closer to reality: how I perceive myself or how others perceive me. I like to think I have a strong understanding of who I am and consistently present my authentic self to people, but this naive thought is disrupted whenever someone describes me in a way that sounds foreign or not quite right to me.

It’s also disrupted when I misunderstand a fundamental aspect of myself. Recently, I was navigating a tricky situation that caused me a lot of distress and anger. But the experience made me realize something odd: before experiencing it, if you had presented the exact scenario and asked me to guess how it would make me feel, I probably would have responded with something like, “I’d be mildly annoyed, I guess.”

How could I be so wrong? And now that the situation has passed, I find myself looking back and wondering why I was so emotionally invested in the first place. I’m either stubbornly ignoring new information about myself, or I do not understand myself as well as I thought I did. Perhaps it’s simply that humans are bad at assessing how they would react to unfamiliar situations.1

I love asking people to share their top personal values because I’m always pleasantly surprised by their answers, no matter how well I know them—and because I’ve always felt like their answers can help me better understand their motivations, life choices, and other intimate details—who they really are. But recently, I got pushback for the first time in all my years of asking this question. My friend found the question reductive (“the human spirit can’t be summed up into three words”) and insisted that any response a person readily gives is likely inaccurate to the point of being worthless. This seems overly cynical to me, but maybe there is some truth to it. Are we overestimating how well we know ourselves? And are we overestimating the necessity—or even possibility—of self-discovery?

compulsory self-discovery

In James Baldwin’s novel Giovanni’s Room, the protagonist, David, is constantly fleeing from what he has learned about himself—his homosexuality—in hopes of discovering something different. (Ideally, something more palatable to himself and the society in which he lives.) In the end, he realizes he was escaping himself in an attempt to find himself—a futile, if not self-destructive, exercise:

“Perhaps, as we say in America, I wanted to find myself. This is an interesting phrase, not current as far as I know in the language of any other people, which certainly does not mean what it says but betrays a nagging suspicion that something has been misplaced. I think now that if I had any intimation that the self I was going to find would turn out to be only the same self from which I had spent so much time in flight, I would have stayed at home.”

There is no shortage of movies, novels, and other forms of media that obsess over self-discovery at any expense. They urge us, as if it’s a matter of life and death, to find ourselves—our true selves. But they’ve steered us wrong. The quest for self-discovery implies there is a prize ending; a time you’ll be able to breathe out a sigh of relief, or jump up and down with excitement, or throw a party, or in some way acknowledge that you’ve finally done it: you’ve discovered yourself. But in practice, the quest never ends, because fully knowing oneself is impossible. This sounds obvious, but it’s hard to internalize in a culture that treats perpetual self-discovery as a virtue.

The urge to discover oneself is a drive many people experience at some point—and for some, it never really goes away. I’m not sure if this is learned or inherent, but there is wide speculation that it’s the former. In her extended essay A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf curiously notes the scarcity of work about the inner states of writers and artists in the sixteenth century. “Nothing indeed was ever said by the artist himself about his state of mind until the eighteenth century perhaps,” she thinks. “[B]y the nineteenth century, self-consciousness had developed so far that it was the habit for men of letters to describe their minds in confessions and autobiographies.”

Psychoanalyst Erich Fromm had the same thought in one of my favorite books, Escape from Freedom. He traces the seeds of our self-consciousness—in the literal sense, as in the consciousness of our selves as individuals—back to the Renaissance, when Humanity replaced God/The Church as the center of the universe. Suddenly, who you were was not predetermined based on your class, geography, family standing, or whatever basis society used to justify your role in it. Suddenly, who you were was much more up to you—much more up to interpretation, analysis, and discovery.

The idea that we can and should discover ourselves has a rich history, and it does kind of feel like we’re at the height of it now. But is such discovery possible? When people talk about self-discovery, it’s either implied or entirely overlooked that the end goal is the complete knowledge of oneself.2 It’s a Sisyphean task parading as an achievable goal. It dooms us to failure from the start.

complete vs. accurate self-knowledge

A complete understanding of yourself would require gathering and evaluating an incomprehensible (and unattainable) amount of data, like what everyone thinks of you at each stage of your life and how you would react in every possible scenario. How would you respond to life-or-death situations? What about in rare and unusual circumstances? How might your reactions differ at various times in your life? If you’re lucky, you will never know how you would respond to being stranded on an island—but that situation would yield information about yourself that is, at the very least, interesting to know, but more importantly, crucial if you want to completely understand what kind of person you are. You could guess based on the knowledge you currently have about your personality and background and past experiences, but you won’t really know your response until you live this nightmare island scenario.3

Since we can’t gain a complete understanding of ourselves, we have to settle for the next best thing: an incomplete understanding that requires constant updating—hopefully in the right direction—as we continue to take in more information from our peers and life experiences. The key phrase here is “in the right direction.” One could interpret information incorrectly and update further away from reality. One example of this is when victims of abuse eventually believe their abusers’ character attacks, which leads to feelings of worthlessness and insecurity. An opposite but equally problematic example is when narcissists surround themselves with people who feed their egos, which protects (and strengthens!) their already unrealistic sense of self.

Here’s how I see it: complete self-knowledge is impossible, so we must accept that self-knowledge will always be incomplete. It’s not like we begin at 0% self-knowledge and then embark on an Eat, Pray, Love journey to bring us to 60% self-knowledge and then hopefully, somehow, reach 100% before we die—no matter how tempting this mentality might be.4

From Joanna Biggs’ bibliomemoir, A Life of One’s Own: “There are moments in life where you shock yourself by what you want and what you’ve done, and they stop you from being able to trust yourself. You may not even be on the wrong path, but your ease in your own reactions has gone.” There is no such thing as complete self-knowledge because we are constantly changing. If our hearts and minds are gentle and loving and open to it, we could learn a thing or two about ourselves—but that thing or two might change with time, only for us to have to relearn it, again and again and again. Maybe that’s what makes the often failed attempts at self-discovery so tragic. You can take drastic measures in an attempt to find yourself, only to realize in the end that there is no finding yourself—there is only gaining incremental knowledge about yourself that could change in an instant depending on your circumstances.

Perhaps a more productive framework, then, is to focus on the accuracy of our self-knowledge, also known as self-awareness. How close to reality is your understanding of yourself at this moment? To what extent are you deceiving yourself when you call yourself a loser, ugly, dumb, or the smartest person in the room? Do you know your values, and how others perceive you? Are you running away from what you have already learned about yourself? Are you open to the fact that you will change?

While the quest for the completeness of self-knowledge implies an end that does not exist in reality (and therefore oppresses us), the quest for the accuracy of self-knowledge recognizes that we are constantly changing (and therefore liberates us).

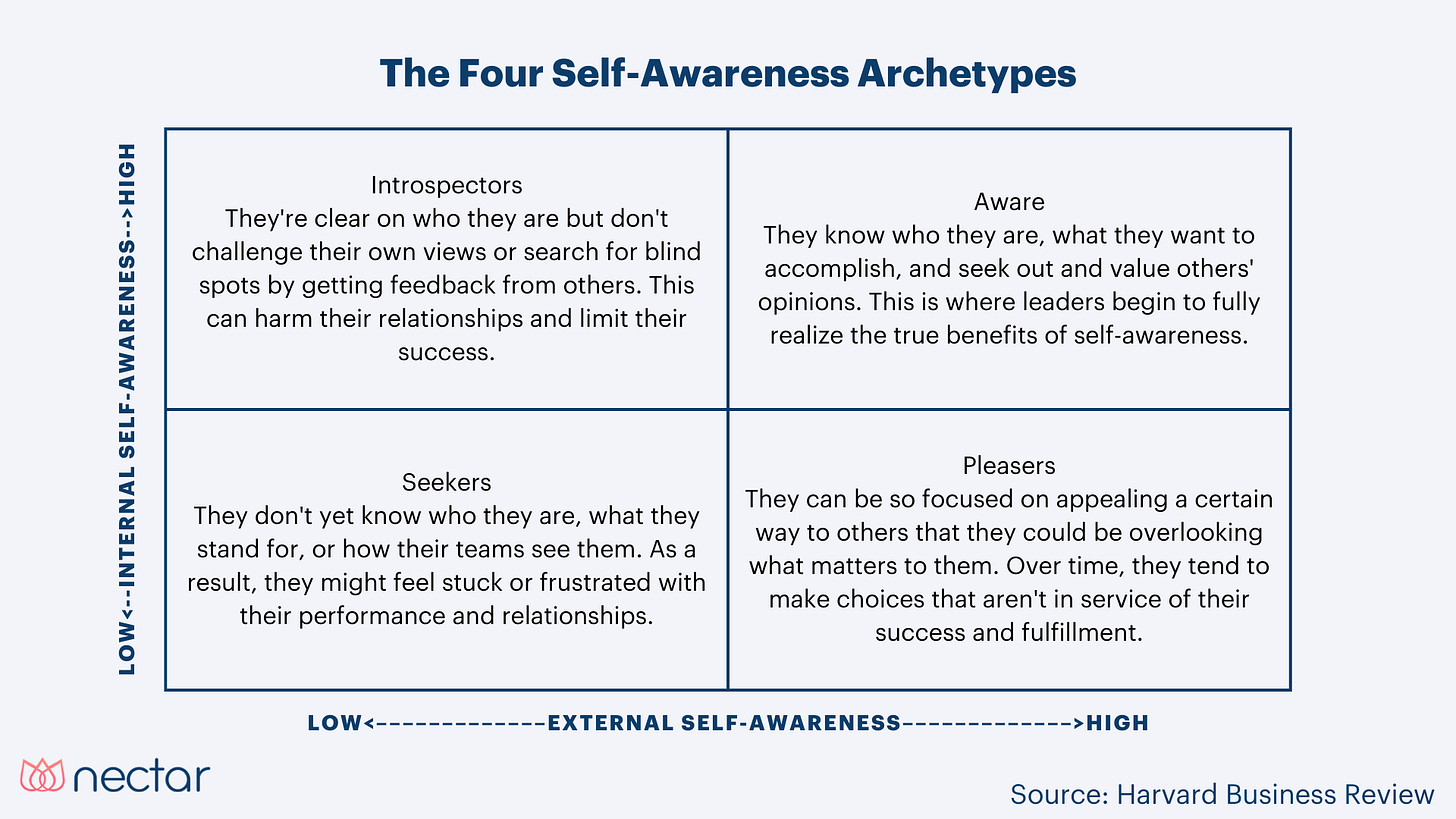

I don’t see accuracy as binary as I do completeness. It’s a bit more complex. Research conducted by organizational psychologist Dr. Tasha Eurich suggests that each person falls on a spectrum from high to low internal self-awareness and high to low external self-awareness. (While 95% of the people she studied believed they fit the criteria for high self-awareness, just 10% to 15% actually did; it’s a rare quality.)

Dr. Eurich defines internal self-awareness as “how clearly we see our own values, passions, aspirations, fit with our environment, reactions (including thoughts, feelings, behaviors, strengths, and weaknesses), and impact on others.” Meanwhile, external self-awareness is understanding those same factors, but in terms of how others view us. The two types of self-awareness are independent of each other, but they are skills that can be developed. One way to become more self-aware is to introspect correctly, by asking “what” questions instead of “why” questions when trying to better understand yourself. The former helps you find solutions, the latter causes rumination.5

Dr. Eurich’s study is targeted at the corporate world, but her findings are relevant to all aspects of our lives. I think of people who score high on both internal and external self-awareness as being integrated. They have insight into themselves.

fracturing the self

At the start of this post, I noted my belief that I present my “authentic self” to people. But what if I’m thinking about the self all wrong? An authentic self implies the existence of an inauthentic self and, thus, some sort of fracturing of the self. What if there’s is only Self, rather than the dualities we agonize over: higher vs. lower, instinctual vs. intellectual, controller vs. controlled, good vs. bad, current vs. desired?

In his essay “Zen and Control,” philosopher Alan Watts writes at length about the issues that arise from fracturing our sense of self in this way:

The problem is this: man is a self-conscious and therefore self-controlling organism, but how is he to control the aspect of himself that does the controlling?

It is of great interest that we cannot effectively think about self-control without making a separation between the controller and the controlled, even when—as the word “self-control” implies—the two are one and the same.

I have not stopped thinking about this since I read it months ago. But it opens up a whole new can of worms about the nature of the self and consciousness, an impossible question that has been debated fiercely for a long, long time—one I certainly won’t be able to figure out in a blog post, despite my obsession with it for years now. Perhaps more on that some other time.

Thank you for reading! I’d love to hear your thoughts about the points I made regarding self-discovery and the self. Do you disagree? What’s your experience?

Have you ever asked someone how they think they would feel if [X] happened, only to be completely surprised by their response? In these instances, it’s always fun to guess whether you (a) discovered that person’s blindspot about him or herself, or (b) you don’t know that person as well as you thought you did.

Some good questions to ask when someone tells you they want to discover his or her real self: What are you hoping to find? Is there something you’re scared you might find? How will doing [X] actually help you discover yourself? When will you know you’ve discovered yourself? What about yourself is not real, right now? Too often I’ve seen people make drastic changes in their lives in an attempt to find out who they are—but their goal was always far too abstract, vague, and unclear to ever be useful.

There has been much debate about how well personality traits can predict behavior. How can we know which soldiers will fight and which will flee? Well, we can’t yet: studies have not found a consistent correlation between personality traits and combat valor. This is also the case for more casual situations, like whether an extrovert will be the life of the party. The consensus seems to be that unless the personality traits under consideration are specific, limited, extreme, and/or observed over time, it’s hard to say how they influence behavior.

It’s natural to use storytelling, or some sort of rational framework, to make sense of our messy, and contradictory pasts that are filled with impulses and motivations that are mysterious or invisible to us. It’s only human.

Dr. Eurich’s take on introspection is interesting, but it makes sense. Her research found that the way people introspect makes a big difference in their self-awareness, job satisfaction, and overall well-being. Most people introspect by asking themselves why they did something or feel a certain way, and since we don't have access to many of our unconscious thoughts, feelings, motivations, or even physiological processes, our brains tend to invent answers that feel true—which we end up believing in with little reservation. (Her example is great: “For example, after an uncharacteristic outburst at an employee, a new manager may jump to the conclusion that it happened because she isn’t cut out for management, when the real reason was a bad case of low blood sugar.”) Her research team analyzed the interview transcripts of the highly self-aware participants and found that they tended to ask themselves questions about what happened and what they could do moving forward—a much more effective approach to introspection.

Great post. I took good 30 mins to understand the quote by Alan Watts, it was too intriguing. The idea of the contoller and the controlled. Our whole life is a battle between the two, most of the times we seek to control ourselves, clearly we forsee a division between the two. The times when we are at peace, both the entites seem to converge. This also reminds me of Jiddu Krishanmurti quote, "The highest form of intelligence is to observe yourself without judgement". Now I think I somewhat understand what he means, we should seek to understand the divided controller and controlled. Thankyou for this!

My reaction to "self-discovery" as an explorable concept is that there are multiple things being bundled into that package, all things you allude to, but there's confusion being caused by their interchangeability in discourse.

I think it's probably a cultural romantic notion foremost; it's not so much that people have a strong innate need to "find themselves" versus desiring others see them as a persona package characterized as "on a perpetual journey of self-discovery" etc. Much of this definitely seems to be having a requisite cultural milieu for it. Secondly, as you say, it seems to be a coping strategy for some, plus or minus in tandem with the above; people who are avoiding from some unpleasant obvious truth about themselves.

Thirdly, "self-discovery" as a packaged product designed to foster a sort of "useful" personality for someone else's convenience. Looking at that Four Self-Awareness Archetypes, I'm reading it thinking "why does it feel like someone is trying to make me feel bad for not fitting very neatly into the upper right box, OH Harvard Business Review, got it." This kind of thing is very unsettling to me.

All said I think it's good and healthy to be intensely curious about the nature of your own consciousness but I don't know we should encourage people to either make that their entire personality, engage the concept superficially for entertainment, or use it as a cudgel against people deemed insufficiently self-curious.