you owe it to all versions of yourself

it's time to bring consciousness discourse to the mainstream

“We do not grow absolutely, chronologically. We grow sometimes in one dimension, and not in another; unevenly. We grow partially. We are relative. We are mature in one realm, childish in another. The past, present, and future mingle and pull us backward, forward, or fix us in the present. We are made up of layers, cells, constellations.”

― Anaïs Nin

Severance is the best show I’ve seen in years. Seriously, when was the last time a show was this widely beloved? Game of Thrones, Breaking Bad, The Walking Dead, the first season of Westworld? Maybe Succession?1 It’s been a while.

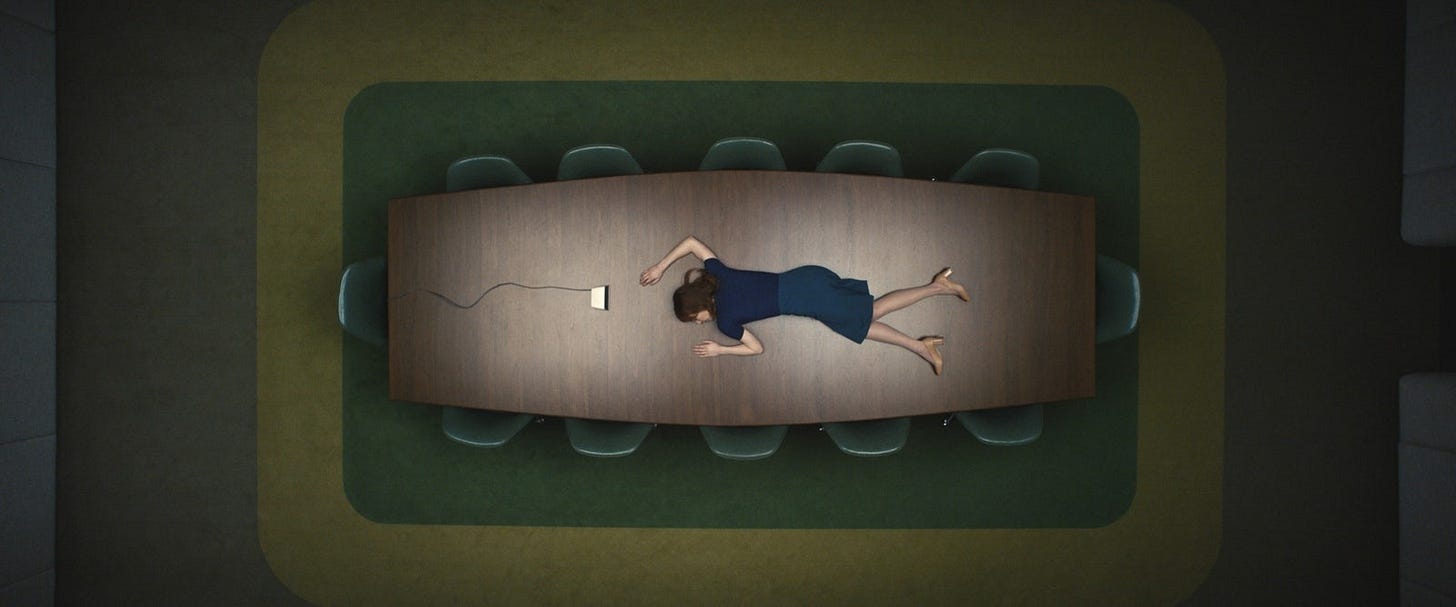

In the world of Severance, employees of Lumon Industries, a mysterious, cult-run biotech company, can elect to undergo a procedure to sever their consciousness. This allows them to separate their work and personal lives while remaining in the same physical body, taking work-life balance to a new level. When a severed employee enters Lumon, he becomes the work version of himself (called an “innie”), retaining no memories of his personal life. Once he leaves work, he reverts to the non-work version of himself (called an “outie”), retaining no memories of his work life. Unsurprisingly, outies have more rights than innies.

The show is great for many obvious reasons: the cinematography is beautiful, the acting is phenomenal, the attention to detail is meticulous to an absurd degree, and the storyline is refreshingly unique. What I love most about it, however, is the questions it raises about the nature of consciousness and the resulting ethical implications. Severance presents itself as a show about work-life balance and corporate corruption, drawing people in with safe, mainstream topics. But before they know it, fans are instead forced to grapple with challenging philosophical questions about consciousness—a less culturally palatable discussion, but a much more important one given the rapid development of AI and humanity’s inevitable trajectory toward transhumanism, for better or worse.

Of course, Severance is not the first TV show to explore consciousness, but it might be the most popular contemporary show to do so—and have a real influence in shaping mainstream discussions around it. (Although I’d be remiss not to mention my favorite episode of Black Mirror, White Christmas, which also forces viewers to contend with questions about who benefits from certain definitions of consciousness. Imagine a digitally cloned version of yourself created to be your perfect personal assistant, but it’s trapped in an egg-like object and claims to hate its life. Is it conscious? Does it have rights? Can a digital clone really feel “hatred”? What is your obligation to this digital clone? Where does your sense of you begin, and where should it end? If you like Severance, you’ll appreciate this brief subplot in the episode.)

My immediate reaction to the procedure in Severance is that it’s unambiguously unethical—and, frankly, a logistical nightmare. Does my innie have a right to treat my body in ways my outie wouldn’t like, or vice versa? Who gets to decide whether to continue employment: my innie, who actually does the work, or my outie, who relies on the income for survival? I can’t confidently answer any of these questions, and I’d be suspicious of anyone who does. But try bringing the conversation up with friends, and you might be surprised by the number of people who don’t consider this a serious moral problem, or who dehumanize innies. (This is why I’m so excited that a mainstream show is touching on challenging questions about consciousness; people will be forced to think about it in ways they may never have considered before, and this has profound consequences for our understanding of ethics.)

Thankfully, the procedure is not possible—or it won’t be in my lifetime, at least—so what does the innie vs. outie debate mean for us, in the real world, today?

I have always been drawn to the idea that people have multiple selves (i.e., all of our future, past, and current selves) and that each self is just as real as the one with which you currently identify most. This means our actions should take into account the rights of each one of these selves. What might this look like in practice?

Future selves: The person you will be tomorrow, in two years, in two decades, etc.

How will Tomorrow You feel about getting blackout drunk tonight in front of your coworkers?

What would a 60-year-old You with two children, a wonderful partner, and an appreciation for life2 think about your decision to start a habit that is destructive to your health because you currently believe life is meaningless?

Past selves: The person you were yesterday, as a teenager, as a child, etc.

How would 10-year-old You feel about the person she is today?

How would Teenage You feel about the cruel or unforgiving ways you think about her and her decisions? How might she feel if you forgive her?

How would Yesterday You feel if she learned that the project she excitedly started has already been abandoned?

Current selves: The person you are in front of friends, coworkers, family, in a romantic relationship, etc.

Do the different versions of yourself feel unified? Or are they jarringly disparate, creating feelings of inauthenticity?

In a way, the person you consider You right now—the one making all the decisions that (1) affect future versions of yourself and (2) characterize past versions of yourself—is like the outie in Severance.3 In our world today, all these other selves are treated like innies: at best, they’re disregarded; at worst, they’re completely dehumanized; and at all times, they are subject to the whims of their outie.

My line of reasoning might sound familiar to those who know about Internal Family Systems (IFS) therapy, an approach to psychotherapy that sees “every human being as a system of protective and wounded inner parts led by a core Self.” Many of these parts, especially the wounded ones, are our past selves, or the innie according to my logic above. Each one has needs, but they are often ignored in favor of the needs and preferences of the current self, or the outie. (On the flip side, my line of reasoning might sound really weird to those who don’t know about IFS. If that’s you, I highly recommend you look into it. It’s super cool! I like The Integral Guide, but there are many other resources too.)

You might also notice that my claim (that our future selves matter just as much as our current selves) is similar to the one made in William MacAskill’s book What We Owe The Future, which argues for longtermism, or the idea that we have a moral imperative to act in a way that benefits future people because they count just as much as we do.

The IFS model of therapy might be relatively new, but the idea that people have multiple selves certainly is not. In her essay Second Selves, Elisa Gabbert references Virginia Woolf’s diary entries about people’s multiple states of consciousness. In April 1925, Woolf wrote, “My present reflection is that people have any number of states of consciousness: and I should like to investigate the party consciousness, the frock consciousness etc.” Then in the margins of that diary entry: “Second selves is what I mean.”

Regarding Woolf’s idea of multiple selves—and the notion that diaries never quite capture a person’s entire self4—Gabbert wonders:

Who is Woolf lying to, if she is lying, in these diaries? Herself, a little bit, the second self that is the diary, and the future Virginia, who might as well be another person entirely. In 1919, she writes, “I am trying to tell whichever self it is that reads this hereafter that I can write very much better.” Later that year: “What a bore I’m becoming! Yes, even old Virginia will skip a good deal of this.”

At the age of thirty-eight, she writes: “In spite of some tremors I think I shall go on with this diary for the present. I sometimes think that I have worked through the layer of style which suited it—suited the comfortable bright hour after tea; and the thing I’ve reached now is less pliable. Never mind; I fancy old Virginia, putting on her spectacles to read of March 1920, will decidedly wish me to continue. Greetings! my dear ghost; and take heed that I don’t think 50 a very great age.”

It seems we can’t help but imagine an audience when we write. Because a journal makes the self external, the self counts as an audience.5

In much of her writing, Woolf seems to be in dialogue with multiple versions of herself—past, present, and future. In 1924, she wrote: “And old V. of 1940 will see something in [this book] too. She will be a woman who can see, old V., everything—more than I can, I think.”

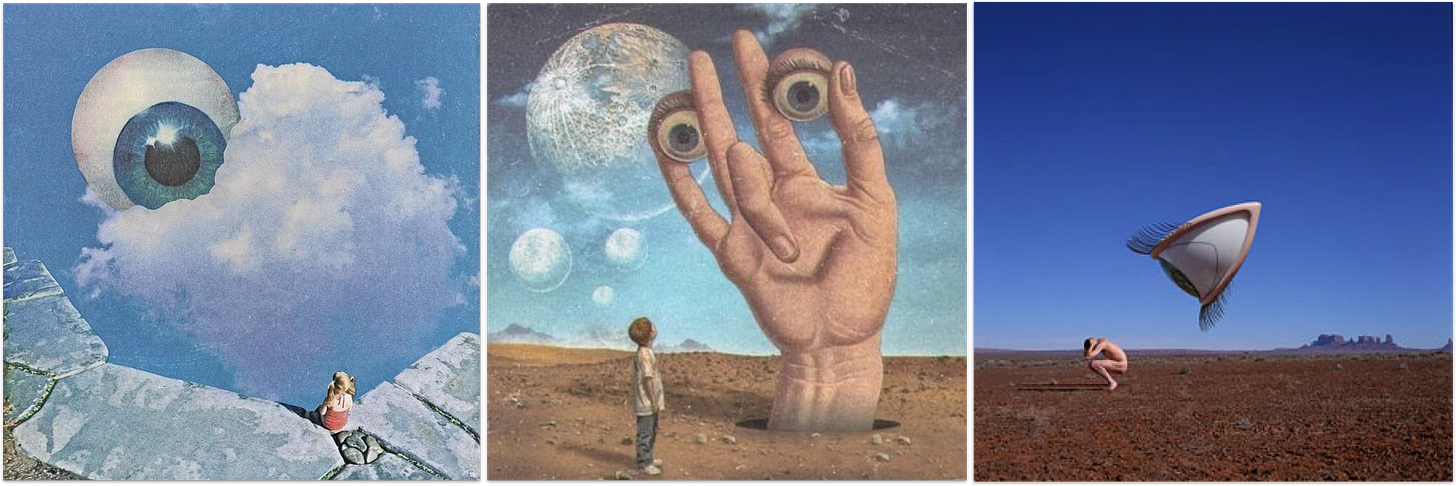

Ultimately, I think all these ideas—second selves, longtermism, IFS, Severance—tie back to questions about consciousness. What is it?6 Is it produced by the brain, or is it a fundamental aspect of the universe and therefore something our brains can “tune into” (like radio stations)? Is it the foundation of reality, implying matter is produced within and by it? Who has it? Can objects have rudimentary types of consciousness, a la panpsychism (my favorite theory to ponder)? And most importantly: how do answers to these questions change our understanding of morality and ethics?

The vibe shift is here, and I’m not the only one who has noticed or is excited about it. From Scott Britton:

The great awakening seems real. I probably get 2-4 messages a week from childhood friends, former business contacts and previous skeptical friends who now want to talk about consciousness. This has picked up from a year ago where at times I felt like I was banging a consciousness drum into a void. It’s exciting. I do believe there is an objective shift going on.

To be clear, I think it’s very likely that we’ll never fully know what consciousness is. (See footnote #6 for an explanation.) Regardless, it’s a topic I’ve always loved and will continue to obsess over, and I hope whatever temporary answer we land on will lead to better outcomes for all beings.

Don’t say Ted Lasso, or I’ll block you.

It’s probably good practice to imagine your future self in a positive light. Your future self deserves that!

Interestingly, one of my friends brought up the idea that God is an outie, and all of his creations are innies. There are so many ways to apply the outie vs. innie framework.

More from Gabbert’s essay Second Selves:

In his preface to A Writer’s Diary, the volume of extracts from Virginia Woolf’s diaries that he edited, Leonard Woolf remarks that, even taken in full, “diaries give a distorted or one-sided portrait,” because “one gets into the habit of recording one particular kind of mood—irritation or misery, say—and of not writing one’s diary when one is feeling the opposite.” Max Brod writes something similar in his postscript to Kafka’s diaries, which he published against his friend’s wish that they be “burned unread”: “One must in general take into consideration the false impression that every diary unintentionally makes. When you keep a diary, you usually put down only what is oppressive or irritating. By being put down on paper painful impressions are got rid of.”

How fun is the thought that you can have two selves at once: the one writing, and the one witnessing the writing?

By the way, this Quora response to the questions “Is there any conclusive proof that the brain produces consciousness?” and “What rules out the case that the brain acts as receptor antennae for consciousness?” is close to what I believe:

as someone who constantly thinks about the past & future versions of myself, i loved this!! the analysis of severance & how it’s connected to those ideas was also so smart. what a great read!!

Cool piece tying things together, i hope your friends end up interested in consciousness though i think it will always be a static percentage - some people want to play exclusively 'innies' the consciousness and some people like talking 'abouties' the consciousness.

I see you mentioned IFS I didn't quite make that connection though maybe they will head that direction in the show, especially with the brother-in-law author as a stepping stone to ease people into this kind of talk. My first thought was that the innie represents an inner child abandoned and attempting to do reintegration, but it also makes sense that future seasons will start looking very IFS-like too.

I really got stuck on the re-integration part in the story, I wonder if the "permanently severed" cases are the ones where they forced reintegration and they failed. Any thoughts on this?